Shifting Careers to Autonomous Vehicles

This article was originally posted at Medium.

The new year is a time for reflection on our past and planning for the future. Within that spirit, I would like to take the opportunity to recount my journey within the industry as deep learning (DL) / computer vision (CV) engineer.

In January of 2017, I was working in a company called TrueAccord, located in San Francisco. I was building traditional recommender systems using time series and tabular data. At that time the internet began to flood with blog posts and papers describing these new cutting edge deep learning models which were even able to outperform humans. My passion was soon diverted to this exciting new field.

While I did have some knowledge of deep learning, my hands-on experience was rather limited. Graduate school gave me little opportunity to apply machine learning models, but fortunately, I discovered Kaggle, which allowed me to nurture my deep learning expertise. Eventually, I was able to attain the title of Kaggle Master, achieving a gold medal in the Ultrasound Nerve Segmentation challenge. This was the first challenge where the deep learning architecture UNet was widely used by the Kaggle community. It was also the first challenge in which soft dice was used as a loss function for a segmentation task.

Prior to 2017, Kaggle was focussed mostly on hosting tabular data competitions. The winning solutions typically involved the stacking of xgboost and other classical ML algorithms. Few deep learning algorithms were able to supersede such techniques.

Everything changed in 2017. DL became more mature and moved from academia to industry. Kaggle competitions jumped on the bandwagon and imaging-related challenges became more prevalent.

I enjoyed my job at TrueAccord, but I wanted to move to a position where I would work on deep learning related tasks.

The problem was that my repertoire of skills was not necessarily conducive for such a change:

My major was Physics and not Computer Science.

- I had only one year of industry experience.

- I did not have any machine learning related papers in my resume.

- I did not do any computer vision projects at my job.

- My deep learning knowledge was limited.

Basically, I was in the same situation as any other person that is trying to switch the direction of his or her work.

Consequently, I had to approach my dilemma similarly to anyone in my position. The approach is rather simple: you go to the interview, if it works, you are done, if not, you study what you did not know, and repeat. The hope is that success is achieved within a finite number of iterations, you will get lucky and get the desired position.

Throughout this period I continued to refine my deep learning skills; reading papers, blog posts, and, of course, participating in deep learning competitions.

In March 2017 my work began to pay off when my friend Sergey Mushinsky and I finished 3rd out 493 in DSTL Satellite Imagery Feature Detection Challenge and split $20k of the prize money. After that challenge, I started to feel comfortable with binary image segmentation, and multispectral imagery, which you would typically find in satellite imagery. (Blog post describing the solution, preprint, code)

I used the prize money to buy a second GPU, which in turn made me realize that Keras was not working well with a multi GPU setup. I switched to PyTorch, which has remained my DL framework of choice. Success did not come easy in all walks of life, however. During that same period, I had failed an onsite interview at Descartes Labs, and a few technical screens. I knew I needed to keep working to improve my skill set.

Somewhere around that time, I was invited for the onsite interview with NVidia, which I also did not pass. One of the issues that I had was my limited knowledge of how 2D object detectors work. Luckily DSTL started Safe Passage: detecting and classifying vehicles in aerial imagery challenge that focussed on 2D detection. They decided not to host at Kaggle, but to use their own platform.

There was an important rule in that competition: “Everyone can participate, but you need to have a passport and live in some limited set of countries to be able to claim the prize money.” I lived in San Francisco, I paid taxes in the US, but due to my Russian citizenship, I was not eligible for the prize. I knew about that unfortunate fact, but the competition still provided invaluable practice with object detectors, so after working diligently I was able to finish second in the competition.

The progress of data science proceeds largely based on the collaboration of an extensive international community. I voiced my opinion on Facebook and Twitter on how I believed DSTL’s rules were counter to these ideals, but as the dust settled I cleared this from my mind and moved on. Somehow this story followed me and was picked by Russian news. Soon I found my face on the front page of major Russian news outlets and TV channels.

A British defense lab developing tools for MI-6, AI algorithms, a Russian citizen being denied a prize because of nationality. It makes for a good story and Russian media figured this out quickly. At a time, I did not feel comfortable giving an interview on camera, so I refused to talk to the journalists. It did not stop them. They put my profile picture in the background and invited “specialists” on the topic to give their expert opinion.

The journalists even approached my parents, who had no clue about machine learning, competitions, and all the story. My mother told them that parents are essential but that it would be unwise to underestimate the influence of the school teachers. This deflection worked, and journalists moved with their questions to my high school.

One of the top Russian Tech companies, Mail Ru Group, decided to use this opportunity to get some positive PR. They proposed to give me $15,000, which was equivalent to the second-place prize in the challenge. I liked the idea, but I did not feel that it was fair. I knowingly agreed to rules which stated I was not eligible for the prize. Moreover, I was not thrilled to add to my resume that I had been paid to develop AI algorithms for British MI-6. I thought of a better solution. I love theoretical physics and I know that there are always struggles with attaining adequate funding. Hence I asked to transfer the money to the Russian fund that supports fundamental science.

In the end, everything worked well. Mail Ru Group and I got some positive PR. Russian fundamental science got $15k. And DSTL got the motivation to think twice about their rules for ML competitions.

The story got the attention of the Russian audience for a couple of days and died out after this. In the English speaking press, there is only one blog post that talks about it. Maybe this is for the best :)

Soon March turned to June and I still had not found a computer vision job.

The next company on my list was Tesla. The recruiter contacted me because of my Kaggle achievements, which did not happen often. I passed take-home tests, tech screenings, and an onsite interview. The next steps were the background check and approval of my application by Elon Musk. I did not pass. The recruiter told me that I violated the nondisclosure agreement (NDA) and talked at a forum about the interview process. Which was true. I did mention that I am interviewing in Tesla at slack channel ods.ai. I did not share any interview questions there, but technically they were right. As I remember, Tesla’s NDA is rather strict and prohibits discussing your interview process even at a high level.

This rejection made me sad. Working with Andrei Karpathy would be exciting. Even now, a few years later, I feel guilty that I created that unhealthy situation. Hopefully, at some point, I will have a chance to apologize for my behavior.

Next was Planet: Understanding the Amazon from Space competition at Kaggle. The problem was too straightforward to invest a lot of time in it. Multilabel classification on a small dataset. As a result, I merged with a team with six other people. In one week, we trained 480 classification networks and stacked them. 7th place out of 938.

The company that was organizing the competition was called Planet Labs. They had an open DL Engineer position, I asked about it and was invited to an onsite interview. I failed again. The feedback — not in-depth DL knowledge.

It was the middle of August. After seven months of job search, I started losing my typical positive attitude and faith in myself. I just started the interview process with Lyft, but I assumed that it will end up like everything else before it.

I was sitting in front of the window, numbing my sorrows with a glass of cognac. I just got another rejection:

A Googler recently referred you for the Research Scientist, Google Brain (United States) role. We carefully reviewed your background and experience and decided not to proceed with your application at this time.

It started getting me.

But I had an idea. In every bad situation, there is some esoteric move that may work. Most of the rejections had been received during the resume screening stage. As a result, I did not have a chance to show my technical skills. In order to preempt such concerns, I decided I needed to add deep learning publications to my resume.

I reached out to Alexey Shvets, who was a postdoc in MIT and made a proposal:

- Find the next DL conference that has a competition track.

- Train a model, create a submission, get the last place. (I was assuming that if people spend years, working on some problem, it would be hard to be legitimate competition for them)

- Write a preprint or paper on that academic dataset, describing our solution.

He agreed, and we looked for a conference that would suit us. We came across MICCAI that was happening in three weeks. It had a workshop called Endoscopic Vision Challenge with a few computer vision competitions. The deadline was in eight days.

We picked the first challenge, GIANA. The problem had three sub-challenges. In the remaining eight evenings, I adapted the pipeline that I had used in Kaggle competitions, refactored the code, and trained the new models. Alexey wrote reports that described our approach. We were confident that we would be at the end of the leaderboards. Therefore I did not really invest time in the problems. We sent our submissions and reports to the organizers I assumed that this would be the end of our little adventure. This was not the case, Alexey discovered that the workshop had another competition called Robotic Instrument Segmentation with three sub-challenges with an extended deadline that was rapidly approaching in four days. He asked if I would like to give these sub-challenges a shot. I agreed, locked myself away for four evenings and churned out the code, models, and generated predictions for the organizers.

The challenge came with a caveat: one member of the team needs to come to MICCAI and to present the results. Final standing would be announced only at the conference.

I had never been to Quebec City and Canada at all for that matter, so I was excited to go and agreed.

The day of the workshop arrives. I enter the workshop and find a large community of enthusiastic medical imaging experts who all seem to know each other. I do not know anyone, and I cannot start the conversation because I feel comfortable in Deep Learning and Computer Vision in general. Still, all the specifics of the medical imaging were a bit foreign to me.

The presentation of the first challenge started. Teams from different universities presented their solutions. It was hard to judge how good they were, but it was clear that a lot of work was invested in them. It was my turn. I came to the podium, told the audience that I am not the expert in the field, that we did this challenge only as a deep learning exercise, apologized for wasting their time, and showed our two slides.

The organizers showed the results.

- First sub challenge we are first.

- Second sub challenge we are third.

- Third sub challenge we are first.

First overall. (Official press release)

It was the time for the second challenge, one that had its deadline shifted by four days. Different teams presented their solutions. I again apologized for wasting the time of the audience and showed our two slides.

First, second, first. First overall.

I remember that moment to this day. I am standing at the scene. The organizer is preparing a check and some gifts. Alexey and I emerge victoriously, but I can’t help but feel frustrated by the apparent absurdity. How did this happen that some random dude that does not have domain knowledge in medical imaging got first place in both challenges? And yet, people that make money for a living working on medical imaging use much weaker models?

I asked the audience: “Do you know where do I work?” Noone, except one organizer who checked my LinkedIn profile knew. I told them that I work at TrueAccord, a debt collection agency and that I did not train deep learning models at work. I lamented that I was not able to break away from this model because HRs in Google Brain and Deepmind did not even look at my resume.

After that passionate speech, members of the Deepmind’s health team that were in the audience caught me in the break and asked if I would be interested in interviewing for a Research Engineer position on their team.

I believe it was the first time in history when a debt collection agency won competitions in medical imaging. :)

Soon after, I accepted an offer from Lyft, where I currently work. In the interim between TrueAccord and Lyft, I also participated in the Carvana Image Masking Challenge at Kaggle. The approach from the GIANA led me to the bottom 20% of the leaderboard. New ideas were developed, and the team of Vladimir Iglovikov, Alexander Buslaev, and Artem Sanakoyeu finished 1st out of 735. (blog post, code)

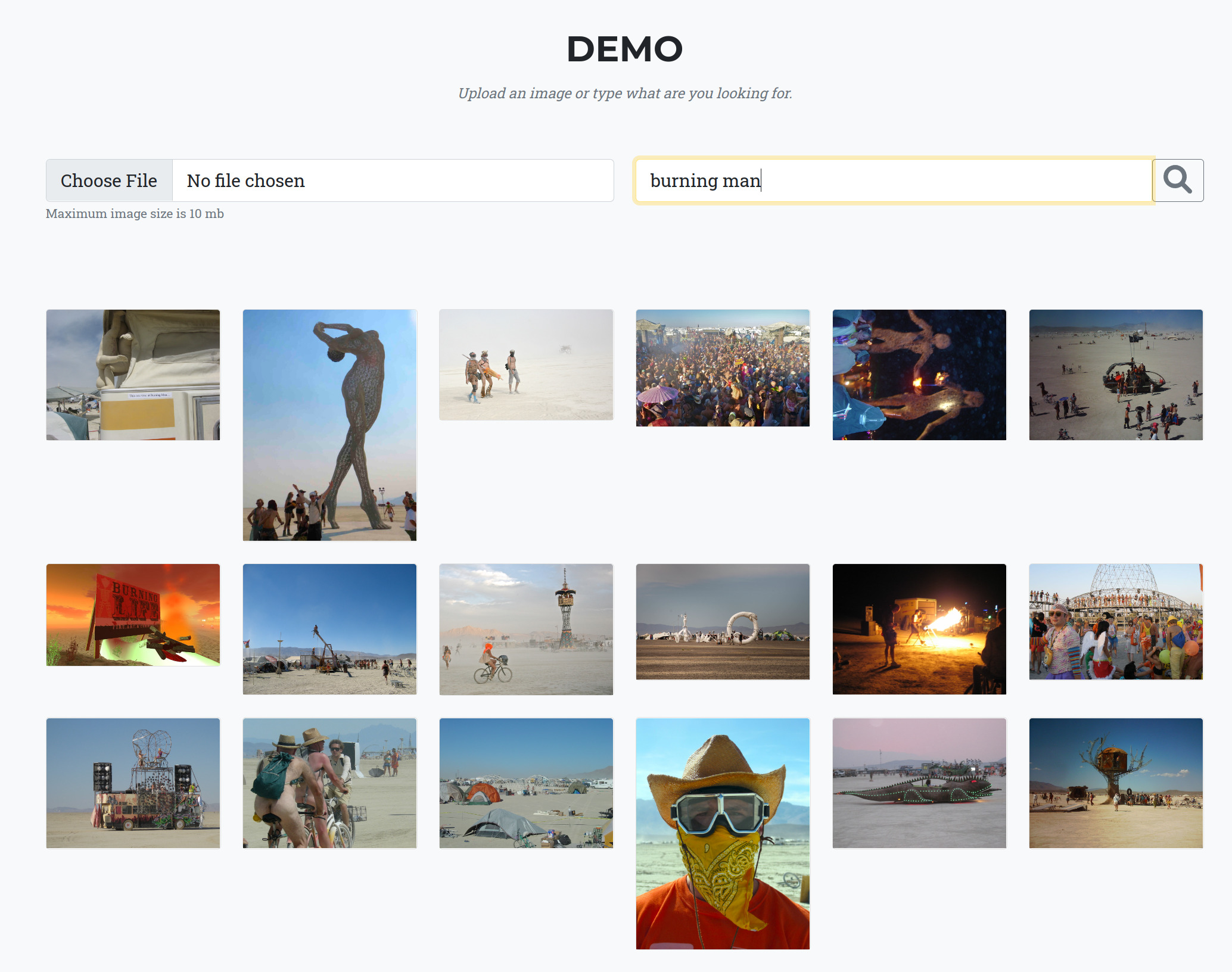

That competition is the first big challenge where the community started using pre-trained encoder in UNet type architectures. It is the norm now, and there are great libraries that allow you to get a variety of different Segmentation Networks with a variety of different pre-trained encoders. But at that time, the idea was relatively new. The challenge led to a preprint called TernausNet, that Alexey and I wrote just for fun, and that is surprisingly my most cited work.

Conclusion

In eight months, I found an excellent job in the field that I was interested in. That time was full of pain. When you are trying new things, you will make mistakes. Every time you fail, you may feel that you are stupid. From time to time, you might start to lose faith in yourself. But remember you are learning something new. And every step you take will move you closer toward your desired goal.

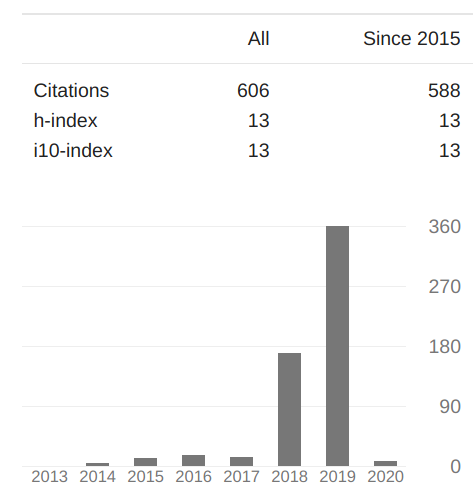

And in the last couple years, I added a few deep learning papers to my Google Scholar profile

Proofread by Erik Gaasedelen.

Comments