Forensic Deep Learning: Kaggle Camera Model Identification Challenge

This article was originally posted at Medium.

About a year ago kaggle.com hosted IEEE’s Signal Processing Society-Camera Model Identification challenge. The task was to assign what type of camera was used to capture an image. After the competition was over, Arthur Kuzin, Artur Fattakhov, Ilya Kibardin, Ruslan Dautov, and I decided to write a tech report describing how to approach this problem and share some insights we acquired along the way. It was accepted to The 2nd International Workshop on Big Data Analytic for Cyber Crime Investigation in Seattle, where I will present December 10th, 2018. In this blog post, I would like to write an extended version of the text.

Arthur Fattakhov, Arthur Kuzin, and Ilya Kibrdin were part of the team that finished second with a score of 0.987.

I was a part of the team that finished 9th with a score of 0.985.

Our solutions are pretty similar, so we decided to write a tech report. Ruslan, a graduate student in the Big Data Institution at Shenzhen University, volunteered to help me with text, which was crucial for this paper.

In the following text, I will refer to the second-place team’s approach as “our” solution. Furthermore, I will skip some technical details that are not critical to the overall message. The code for the second-place solution is available on GitHub. After the end of the competition, we performed a separate set of experiments using the insights that we developed. The work here is based mainly on this further investigation.

Among the many applications for image processing is that of camera model detection. For instance, in the field of forensics, it may be crucial to know whether an image was taken using a Google Pixel or an iPhone to identify who may be the owner of illicit or incriminating photos or even to determine who is the proper owner of intellectual property. Such a system can also be useful for detecting perpetrators in defamation, libel, or the spread of fake news.

Images in the computer are stored as a matrix of numbers and accompanying metadata. In the simplest case, the camera model should be stored in the image metadata, making camera identification an elementary problem. But image metadata can be unreliable and can be easily manipulated by a nefarious user.

There is another, more complicated, but more reliable approach. After the acquisition, the image in the digital camera will go through a series of post-processing steps, creating an image optimized for image fidelity and memory footprint. These algorithms are pretty sophisticated and highly non-linear. Examples may include demosaicing, noise filtering, fixing lens distortion, etc. Different algorithms are used for various camera models, which means that each of them creates model-specific artifacts that one may use as features for a machine learning pipeline.

And of course, there is plenty of literature regarding the topic. Most of it proposes steps for manual feature extraction with SVM or similar classification algorithms on top of it. For example, the first idea that came to mind when I faced this problem was to take an image, subtract a smoothed version of it, and calculate different statistics of this difference, like mean, median, std, and different quantities and train xgboost on them. One of the first papers on how to do this camera model detection was very close to what I just described. Other articles propose something more sophisticated, but the approach is pretty similar, manual feature extraction based on the domain knowledge with logistic regression, decision trees, or SVM on top of it.

Extending this method to new camera models is also hard. Let’s say we want to do this camera detection for a new, just released model. How much time should it take an expert to figure out what features will help distinguish it from the other models?

Deep Learning approaches, on the other hand, allow for solving both of these problems. In general, Deep Learning is a powerful beast, and if you know how to tame it, it may help you create highly accurate black box models.

When you are looking through the literature and try to understand which approach is “the best,” it is impossible. Nearly every paper tells you that they are state of the art. The way to deal with it is to evaluate different methods on the same dataset. Such a comparison will not give you an answer which algorithm is better in general, but rather, which one is better on a given dataset with a particular metric. It does not mean that algorithm ranking will be the same on a similar dataset, say architectures that are state of the art at CIFAR may not perform well at ImageNet and vice versa. But such a unified comparison is better than nothing.

For the camera detection task, the IEEE Signal Processing Society organized a challenge in which 582 teams had two months and a real-time leaderboard to compare their methods. 582 is a significant number, which ensures that the problem will be attacked with people with different backgrounds and skillsets. Some of the participants make money for a living working on forensics in industry and academia. Others, like myself, have experience with computer vision techniques but were unaware that such a problem as camera identification even existed, and someone is interested in solving it.

The organizers prepared a train set consisting of 2750 images, from 10 cameras - 275 per camera.

Camera models that we needed to distinguish were:

- Sony NEX-7

- Motorola Moto X

- Motorola Nexus 6

- Motorola DROID MAXX

- LG Nexus 5x

- Apple iPhone 6

- Apple iPhone 4s

- HTC One M7

- Samsung Galaxy S4

- Samsung Galaxy Note 3

To make the problem less boring, the organizers used 20 different phones to collect the images: ten for train and ten for the test. This means that during training, your model may learn not camera model-specific features related to the post-processing algorithms, but to overfit to artifacts specific to the particular phone.

Images in the test set were captured with the same 10 camera models, but using the second device. For example, if the pictures of the train data for the iPhone 6 were taken with Ben Hamner’s device (Camera 1), the images in the test data were taken with Ben Hamner’s second device (Camera 2), since he lost the first device in the Bay while kite-surfing.

Moreover, images in the train were in full size, while in the test, only central 512x512 crops were used. The reason for this is that radial distortions are more pronounced at the sides of the image. Some papers showed promising results based purely on the radial distortion features. How much incremental value they could add is unclear, but the organizers decided to prevent participants from exploiting them.

And that is not all. In many cases, images that are typically stored on your computer are affected by different transformations like jpeg compression, gamma transformation, contrast, brightness, resize, etc.

From a practical point of view, it would be nice to have a robust model for such transformations. Following similar logic organizers modified half of the test images with one of the following transformations:

- JPEG compression with quality factor = 70

- JPEG compression with quality factor = 90

- Resizing (via bicubic interpolation) by a factor of 0.5

- Resizing (via bicubic interpolation) by a factor of 0.8

- Resizing (via bicubic interpolation) by a factor of 1.5

- Resizing (via bicubic interpolation) by a factor of 2.0

- Gamma correction using gamma = 0.8

- Gamma correction using gamma = 1.2

Jpeg compression with quality [5, 15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65, 75, 85, 95]

Jpeg compression with quality [5, 15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65, 75, 85, 95]

Gamma Transform with quality [0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75]

Gamma Transform with quality [0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75]

As I mentioned above, there are petabytes of images at different image hostings for which we may extract the camera model. Various competitions at Kaggle have different rules regarding the external data, but in this case, it was allowed. In general, all competitions with allowed external data have a rule enforcing that all participants can also access the data. In any competition of this kind, there is a thread at the forum where participants share what data and pre-trained models they are planning to use.

This competition was an exception. Administrators forgot to add to the rules the sentence about sharing the data. And this changed the game.

What is good about deep learning models is that they typically benefit from the amount of data used for training due to the high capacity. And what is also important, many train labels may be wrong. This is fine. As long as a percent of the incorrect labels is less than 15%, you are fine. More data you use, better your model is.

Participants may not be experts in forensics, but the fact that more data is better for DL they knew for sure. This changed the dynamics of the competition. Typically, at the competition, you are trying to squeeze the most from the given dataset. After some experimentation, you pick a model that performs well, smartly choose your augmentations, explore domain knowledge, spend time developing an intelligent training schedule, loss functions, etc. All of this is important if you do not have any better choice. But we did.

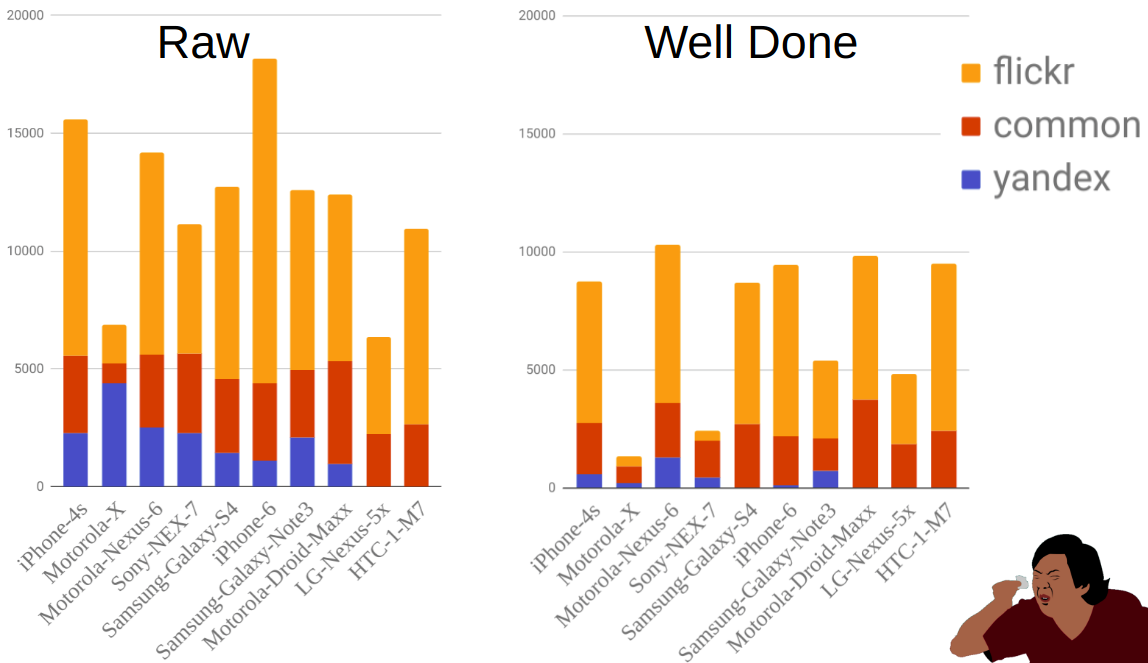

Flickr, Yandex, Fotki, Wikipedia commons were scrapped, and the total volume of the raw image data that the team had was around 500Gb. We could use all this data, but to speed up training and potentially increase the quality of the model we performed filtering.

For training we wanted unmanipulated data, meaning not affected by Photoshop or LightRoom or similar Image editing software, not resized, and in high quality.

First, we deleted images that have Photoshop and LightRoom in the metadata. Second, we removed imaged that has Jpeg quality below 95. Third, we knew that different cameras take pictures in a fixed set of sizes. If the size of the image did not match what we expected, we assumed that it was resized. We deleted images that did not satisfy any of these criteria.

It does not mean that all images that we got were unmanipulated, say someone may use jpeg compression with 10% quality, and after this, apply another jpeg compression with 99% quality. Effectively it will still be 10%, but for our software, it would be hard to find that it is 10 and not 99. I did not want to say “hard,” I wanted to say impossible, but recalled that while working on this problem, I have seen papers that try to identify “double jpeg compression.” And again, I didn’t even know that such a problem exists.

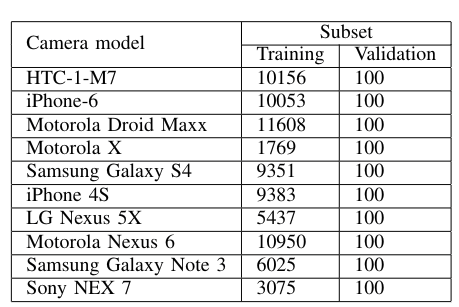

After filtering, we had 78807 scrapped images that are assumed to be original and unmanipulated. Class distribution was uneven. As one may expect, not all cell phones are equally popular, or there is a correlation between the phone model and how often its owner takes a shot and uploads it to the internet. Hence for some classes, we had fewer images.

Camera model classes with the number of samples each part of the dataset. The table presents the final dataset, which contains external and organizers datasets.

Camera model classes with the number of samples each part of the dataset. The table presents the final dataset, which contains external and organizers datasets.

From https://habr.com/company/ods/blog/415571/

From https://habr.com/company/ods/blog/415571/

Overall the pipeline is a transfer learning from ImageNet. You take a pre-trained network, remove the last layer that predicts 1000 classes, and replaces it with one that predicts what you need. In our case, this number is 10. After this, you use categorical cross-entropy for your loss and train the network. The difference between first and 50 places are typically not in the type of the network that one uses but in the training procedure and person who is doing the training. From a practical perspective, Deep Learning is still more alchemy than science. Hence intuition that is developed when one works on different tasks is crucial.

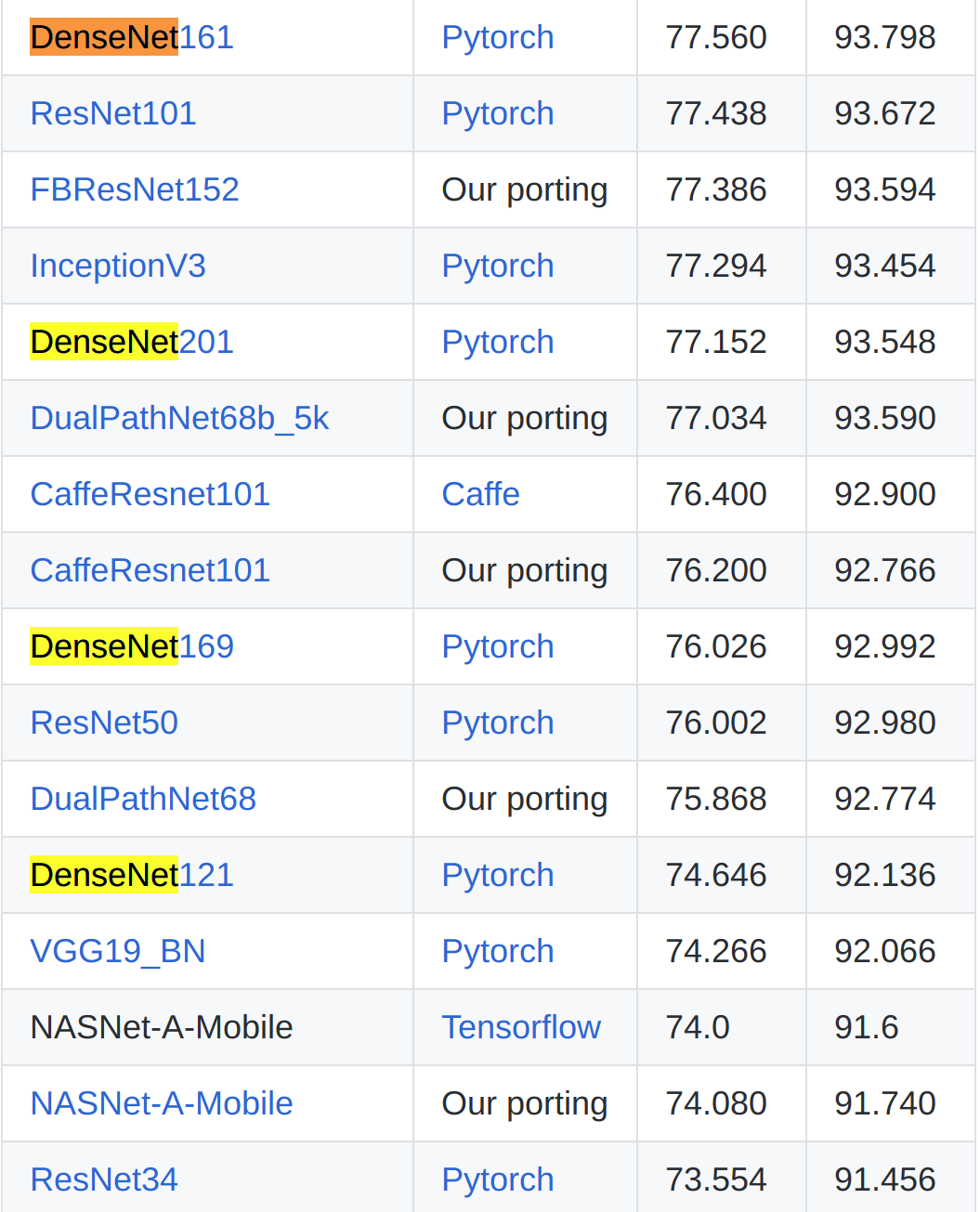

A great list of the networks with weights for PyTorch is the repo by Remi Cadene https://github.com/Cadene/pretrained-models.pytorch. One may get access to the different networks and pre-trained weights using similar API, making experimentation fast. This repo was widely used by the participants in the challenge. Teams experimented with Resnet, VGG, DPN, and all other types of networks.

For this problem, an empirical conclusion was that DenseNet works slightly better, but the difference between teams was so small that if it is true or not is unclear.

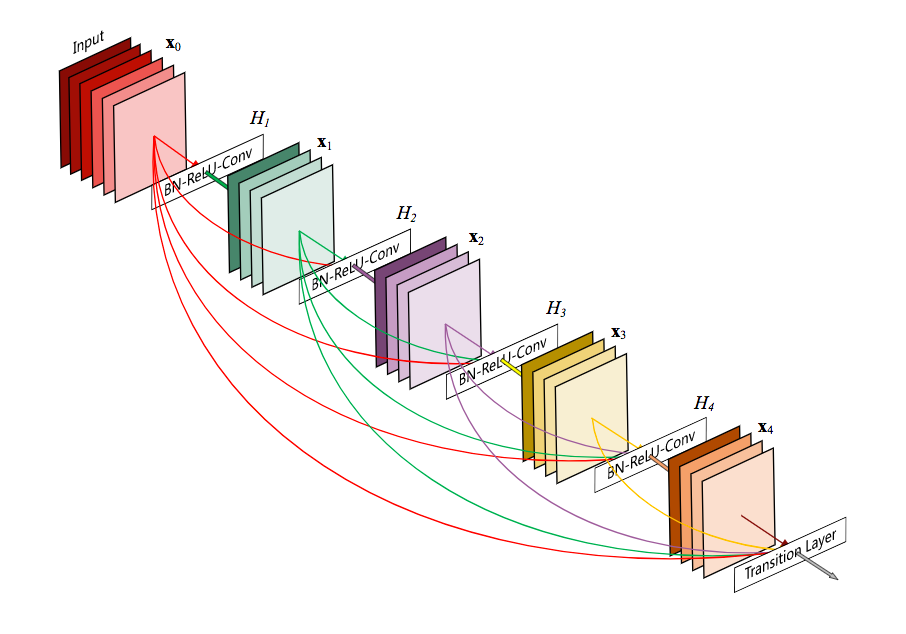

What is DenseNet? DenseNet is an architecture that pushes an idea with skipped connections utilized in Resnet type networks a step further.

https://arthurdouillard.com/post/densenet/ https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.06993

https://arthurdouillard.com/post/densenet/ https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.06993

More skipped connection to the god of skipped connections!

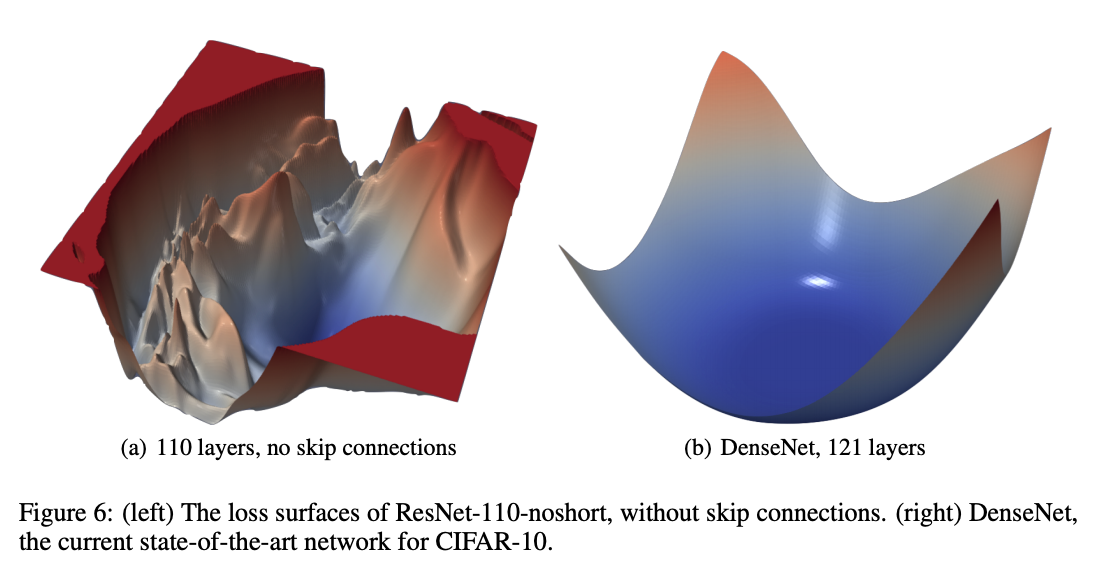

Authors of the DenseNet paper connected all layers within a convolutional block. Skip connections simplify the flow of the gradient, making it possible to train deep networks. Before skip connections became mainstream, dealing with VGG19, which has only 19 layers, was a pain. After introducing them, networks with 100+ layers that can work with very high-level abstract features stopped being an issue to train.

It is also believed that loss surface becomes smoother, preventing training from being stuck in many local minima.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.09913

https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.09913

Besides this, the network is relatively standard. A set of convolution blocks with the batch norm and ReLu layers, having max-pooling between blocks. Global average pooling and dense layer at the end. It is essential to mention that the fact that there is a global average pooling layer allows us to use images of different sizes as input.

Some people believe that DenseNet is always superior to the Resnet because it was introduced later and became the best paper of the CVPR 2017. This is not the case. In the original article, DenseNet showed good results on CIFAR but on the more diverse ImageNet dataset deeper Densenet required to match in accuracy shallower ResNet networks.

Is DenseNet better / worse than Resnet? It depends. In the Planet: Understanding the Amazon from Space challenge, DenseNet, for our team that finished 7th out of 900+, performed better at this camera detection problem. But on the ImageNet, it was worse.

I had a discussion with my collaborators, and someone proposed that skip connections do not only provide good smooth loss surface, but they also decrease model capacity. This may explain why DenseNet performs better in non-diverse problems like CIFAR. Still, one needs to increase the network’s depth to compensate for the loss in capacity on a more diverse ImageNet dataset. Based on this speculation, one may think about the use cases where DenseNets work well is when the dataset is not very diverse and does not require big capacity. Still, discriminative features are a high level, which may require very deep networks.

Does the camera detection task fall in this category? I do not know. Empirically yes, but the evidence is weak.

The standard way to add intelligent regularization to the training process is to use augmentations. Different problems may benefit from various augmentations, and again, better your intuition is better augmentations and their parameters one may choose.

For this problem we used:

- Dihedral Group D4 transformations: Rotations by 90, 180, 270 degrees, and flips.

- Gamma transformation. We choose the gamma parameter uniformly from the [80, 120] range.

- JPEG Compression with the parameters uniformly sampled from 70 to 90.

- Rescale transformation, choosing the scale from the [0.5, 2] range.

In code, using the albumentations library, it can be described as:

import albumentations as albu

def train_transform(image, p=1):

aug = albu.Compose([albu.RandomRotate90(p=0.5),

albu.HorizontalFlip(p=0.5),

albu.RandomGamma(gamma_limit=(80, 120), p=0.5),

albu.JpegCompression(quality_lower=70, quality_upper=90, p=0.5),

albu.RandomScale(scale_limit=(0.5, 2), interpolation=cv2.INTER_CUBIC, p=1)

], p=p)

return aug(image=image)['image']

Left is the original image from my recent rock-climbing trip to Bishop, and right is flipped and a bit darker. The latter is the effect of the gamma transformation. Jpeg compression was also applied, but it is hard to find its effects because quality [70:90] is relatively high.

Left is the original image from my recent rock-climbing trip to Bishop, and right is flipped and a bit darker. The latter is the effect of the gamma transformation. Jpeg compression was also applied, but it is hard to find its effects because quality [70:90] is relatively high.

Organizers told us that they used cubic interpolation for resizing. If we did not have this information, we could use alternate between different interpolations. In general, the competitive ML community uses this trick pretty often, but I did not see it in the literature yet.

Anyway, if we would want to add this alteration, the code would be more complicated, but still, relatively transparent.

import albumentations as albu

def train_transform(image, p=1):

scale_limit = (0.5, 2)

aug = albu.Compose([

albu.RandomRotate90(p=0.5),

albu.HorizontalFlip(p=0.5),

albu.RandomGamma(gamma_limit=(80, 120), p=0.5),

albu.JpegCompression(quality_lower=70, quality_upper=90, p=0.5),

albu.OneOf([albu.RandomScale(scale_limit=scale_limit, interpolation=cv2.INTER_NEAREST, p=0.5),

albu.RandomScale(scale_limit=scale_limit, interpolation=cv2.INTER_LINEAR, p=0.5),

albu.RandomScale(scale_limit=scale_limit, interpolation=cv2.INTER_CUBIC, p=0.5),

albu.RandomScale(scale_limit=scale_limit, interpolation=cv2.INTER_AREA, p=0.5),

albu.RandomScale(scale_limit=scale_limit, interpolation=cv2.INTER_LANCZOS4, p=0.5),

], p=0.5),

], p=p)

return aug(image=image)['image']

Original images have a large resolution. Rescaling them in the full resolution would be unwise. Hence we had two consecutive crops. One before, and one after the resize.

import albumentations as albu

def train_transform(image, p=1):

aug = albu.Compose([

albu.RandomCrop(height=960, width=960, p=1),

albu.RandomRotate90(p=0.5),

albu.HorizontalFlip(p=0.5),

albu.RandomGamma(gamma_limit=(80, 120), p=0.5),

albu.JpegCompression(quality_lower=70, quality_upper=90, p=0.5),

albu.RandomScale(scale_limit=(0.5, 2), interpolation=cv2.INTER_CUBIC, p=1)

albu.RandomCrop(height=480, width=480, p=1),

], p=p)

return aug(image=image)['image']

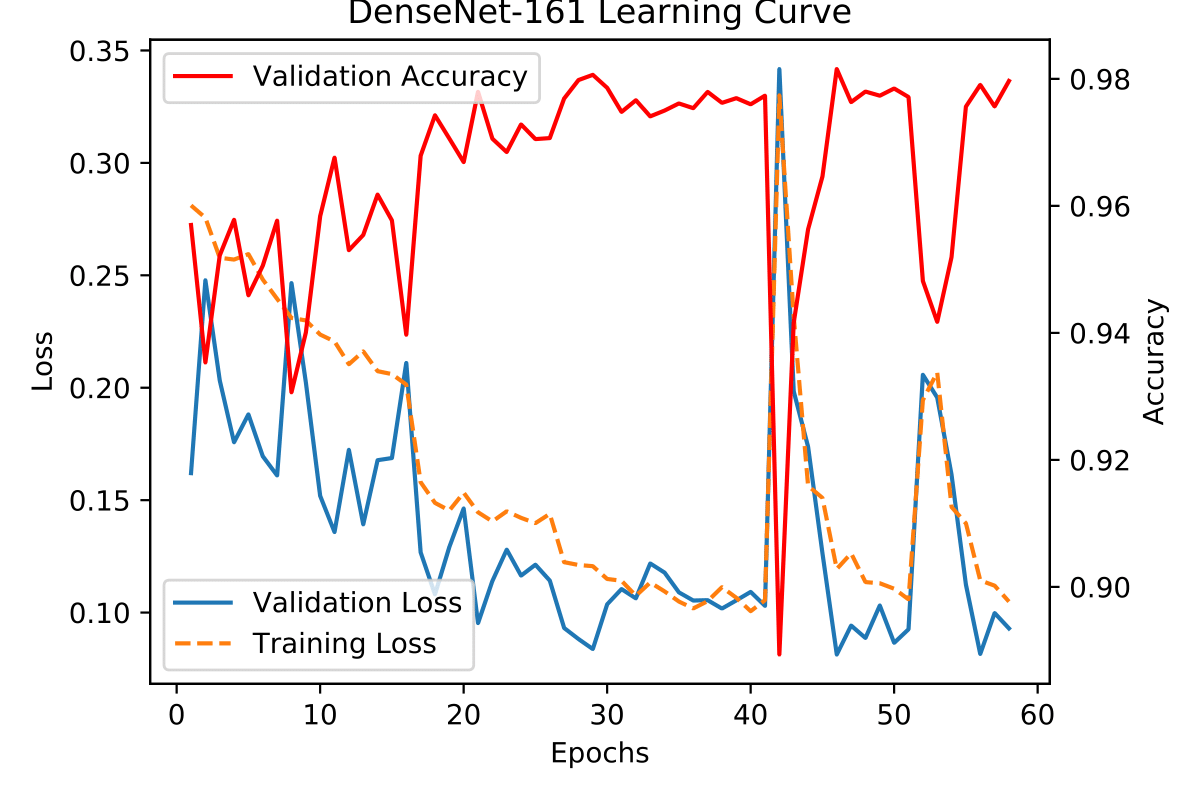

The network was trained for 100 epochs, using Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001.

To get better accuracy, we also used the cyclic learning rate approach when the learning rate oscillates between different values.

As you can guess from this image, the learning rate was decreased around epoch 17.

At the same time, there are two-loss peaks with consecutive decay around 42, and about 53 epoch. During training, networks tend to get stuck in local minimums, and these oscillations help to get out of them.

At the inference time, we performed test time augmentations, averaging predictions from different 480x480 crops of the test image.

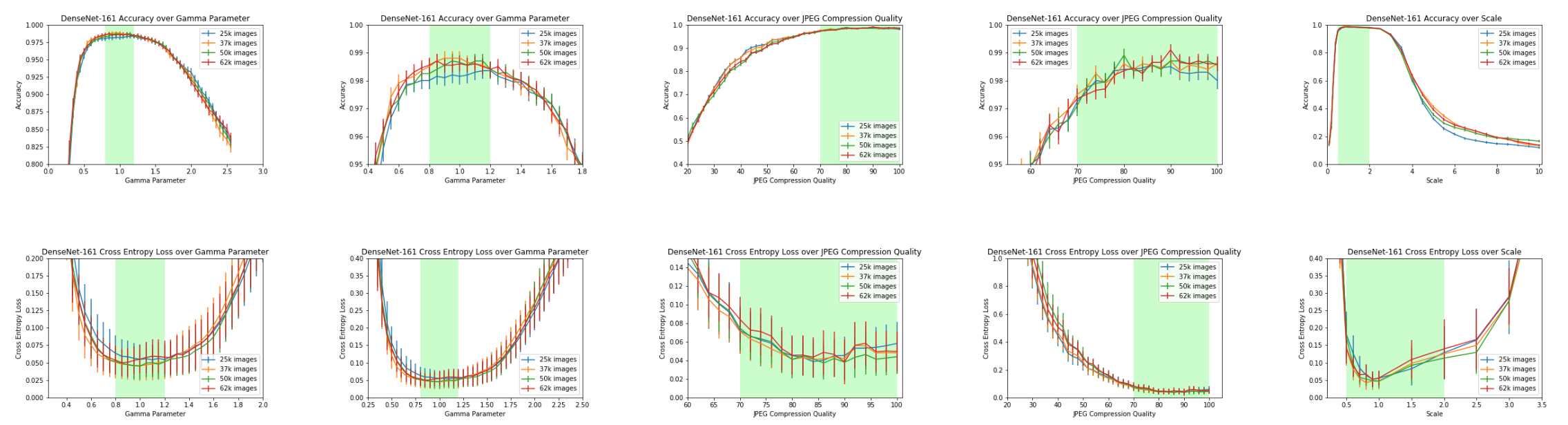

We were also interested in estimating how different transformations decrease the accuracy of the model at the inference time.

In green, we depicted ranges of the parameters that were used during training.

In green, we depicted ranges of the parameters that were used during training.

As expected in the ranges where the model has been trained, no significant decrease in accuracy happens. This suggests that if one uses a Deep Learning approach and has a sufficient amount of data, increasing the ranges of the applied augmentations may lead to a more robust model.

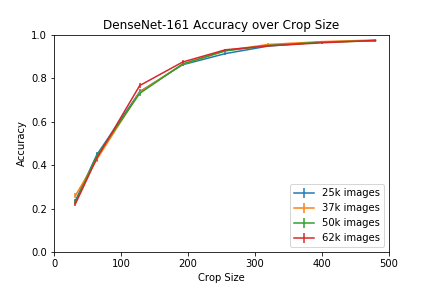

Another question that we wanted to answer is, how does the accuracy perform if we decrease the input size of the crop fed to the network at the test time?

I would think that the features that the network is learning are so local, that there is no need for a large crop, but it looks like it is not the case. To get the accuracy of 10 classes above 90%, one would need to have crops that are at least 250x250, which may imply that post-processing algorithms create long-distance correlations between pixels that networks catch.

We also wanted to verify that when the amount of training data increases, the model’s accuracy goes up. As you may see in the figures, this did not happen. I guess that our lowest data point of 25k is sufficient enough for a good quality model. It may happen that if we needed to detect not 10, but 1000 classes, the rise in the model quality as a function of the train data would be more pronounced.

Summary

- Transfer learning from ImageNet works well even for low-level features like those in Camera Detection tasks.

- DenseNet performed better, but we believe that one may pick any pre-train network from the list by Cadene, and it would perform similarly.

- Applying augmentations during training may help to make the model more robust.

- If you can get more labeled data, get it. In many, but not in all, problems, brute force with a lot of data may be easier to use than complex solutions. Although leveraging domain knowledge can add an important extra boost.

Things that were skipped in the text:

- Does it make sense to add additional output that tells if the image was manipulated or not?

- Tricks like checkpoint averaging.

- How did other architectures perform?

- How to do ensembling for this task.

- How to take advantage of the fact that classes in the test are balanced.

- How to apply pseudo labeling to this task.

- Discussion on what we tried, but it did not work in this task.

- What are the features that the network learned?

- Nuances of the evaluation metric for this problem.

All these topics are important, but I do not consider them ultra impactful, or I would prefer to have a separate discussion on each of them.

P.S. Those at IEEE International Conference on Big Data 2018 in Seattle, the USA on 10–13 December 2018. Stop by the workshop at The 2nd International Workshop on Big Data Analytic for Cyber Crime Investigation and Prevention and say hi :)

Help with editing: Erik Gaasedelen

Comments